On August 15, 1920, our two Argentinean musicians plus the French one boarded the ocean liner Garona and sailed from the Port of Buenos Aires towards the unknown, and their destiny. Unfortunately, Víctor Jachia, sick with an undisclosed illness, died before arriving in Marseilles. Not a good start for their adventure.

The contract they signed with the French impresario was to play for a season at the Club Tabarís Rue de la Canebiere in Marseilles. Each musician was to be paid 50 francs a day. They thought they had won the lottery! But they soon realized that, in the currency of 1920, it was barely $4 a day! A French musician told them, they couldn’t even feed themselves with that salary!

First orchestra in Paris, 1921

Depressed already by the death of their friend and the bad contract they had got themselves into, they decided to get out of this predicament. According to Pizarro, he advised Espósito to stay in Marseilles and wait, while he would travel to Paris to see what could be done. There, he met the Argentinean bandoneonist, Güerino Filipotto, and the guitarist cum pianist, Celestino Ferrer, both of whom were in France since 1913. Soon, Genaro Espósito also left Marseilles to rejoin Pizarro, and with the violonist Pepe Sciuto, they were hired with some reticence by the French impresario, Monsieur Volterra, to play in the cabaret “Princesse” along with some French musicians. This formation was to be known under the name “Orchestra Genaro-Pizarro”.

It was an auspicious start and very successful. But soon they had to dress themselves in operetta gaucho costumes because foreign musicians were not allowed to perform in France unless they were a folklore group! It was a way for the unions of French musicians to control who could play or not. In any case, this fake gaucho costume was not without attraction, and tango was very very popular in France and Europe, especially after the slaughter of the First World War. The European crowds were totally taken by a frenzy of pleasures; it was the Roaring Twenties and tango was part of it.

On June 24, 1921, a publicity poster advertised the same orchestra at the “Pavillon Dauphine” in the Bois de Boulogne, a very exclusive part of Paris.

On June 24, 1921, a publicity poster advertised the same orchestra at the “Pavillon Dauphine” in the Bois de Boulogne, a very exclusive part of Paris.

|

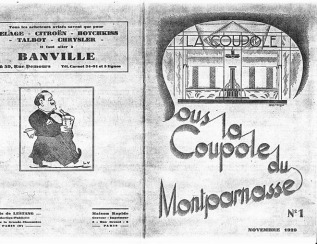

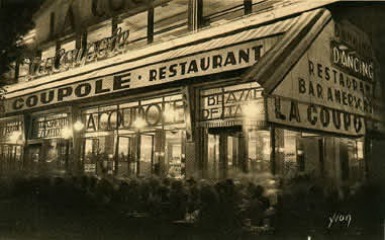

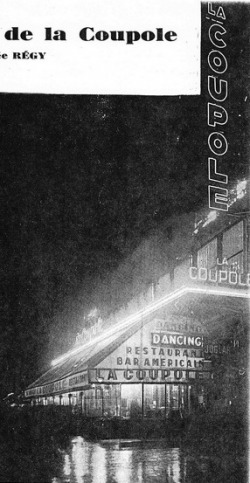

El Tano Genaro at La Coupole 1930 - 1932

|

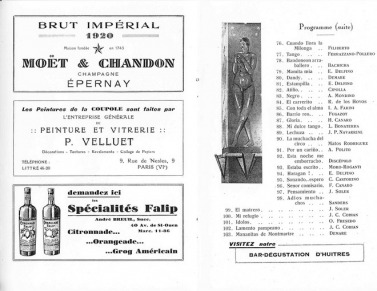

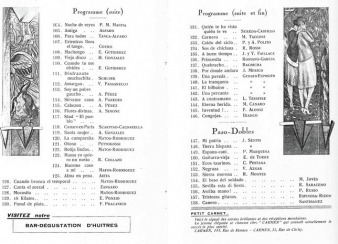

In 1922, Pizarro had to return for a while to Argentina. From this moment on, Genaro Espósito continued alone with his career in Europe under the name of “Orchestre Argentin Genaro Espósito” known as El Tano Genaro. It started with two bandoneons, two violins, piano, guitar and double bass. He performed first at the “Abbaye” in Pigalle and later in the main cabarets of the time in Paris, like “L’Hermitage”, “Club Apollo” and also “Club Daunou” in the Champs Elysées.

El Tano Genaro at La Coupole 1930 - 1932

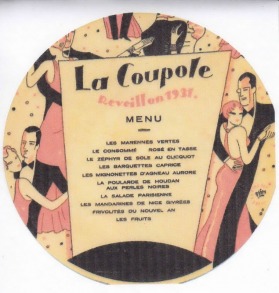

In 1929, "La Coupole" opened in Montparnasse and Genaro played at the opening and then almost until the outbreak of the Second World War. During the summer months, he went on tour with his orchestra to the fashionable sea resorts of France and Italy as well as in Belgium where they performed at "the Palace" of Brussels and the "Kursaal" of Ostend.

In 1934, his celebrated orchestra managed to integrate the very talented Garcia as second bandoneon, at the piano, Miguel Telleria, two violinists – Krik and Carpentier – and LePoutre on double bass. For singers, the Argentine, Juancito Giliberti and the French Merel. Beside his regular work at La Coupole, he recorded for the record companies, Columbia, Gramophone, Fotosonor and Decca.

La Coupole in Montparnasse

|

My father and my mother 1934

|

It is about the same time, my father Genaro Espósito met the young woman who was to become my mother – Jeanne Vent – who sadly passed away before I reached my first birthday. I can imagine the trauma my father went through – his young wife deceased, an 11 month old toddler and his nightly work at La Coupole. But with his resilience as a Porteno, for whom life was never easy, he overcame this trying period of his life. He hired a governess for me and went on with life, perhaps not quite the same after that. |

El Tano Genaro at La Coupole 1934

One night Cobián went to the famous dance club, La Coupole, where his friend of his humble tango beginning, Genaro Espósito, was playing. At the sight of Genaro playing, all his past must have come back at a vertiginous speed, his heart beating faster. Cobián and his wife went to sit in a place a bit hidden from the stage where they could observe the scene without being noticed. Then he signaled the maitre d’. Cobián wanted to surprise his old friend. He asked the man in charge if he could bring Genaro to his table passing himself off as a very important Italian impresario. Genaro walked a bit uneasily toward the table indicated to him. He didn‘t recognize Cobián at first since they hadn’t seen each other for more than 20 years. Our false impresario invited Genaro to his table. Then Cobián very seriously shook Genaro’s hand and presented his wife and respectfully Genaro kissed her hand. Cobián pretended to offer Espósito a contract to play in Italy for a few months in one of his clubs.

After a while, the voice of Cobián reminded Espósito of a voice of his past and as the conversation went on, everything became clear. Genaro exclaimed “You’re Cobián!” Genaro stood up, still incredulous. Cobián started to laugh uproariously and the two old friends fell in each other’s arms with tears in their eyes. They reminded each other of the heroic and bohemian times when they played together along with Zambonini and their mutual friend, the outlandish Arolas, in the different cafes and bars louches of la Boca. But by then, Eduardo Arolas was in his last resting place, the cemetery of Saint-Ouen in Paris where Juan Carlos Cobián and Genaro Espósito together brought flowers to the tomb of their old friend.

After a while, the voice of Cobián reminded Espósito of a voice of his past and as the conversation went on, everything became clear. Genaro exclaimed “You’re Cobián!” Genaro stood up, still incredulous. Cobián started to laugh uproariously and the two old friends fell in each other’s arms with tears in their eyes. They reminded each other of the heroic and bohemian times when they played together along with Zambonini and their mutual friend, the outlandish Arolas, in the different cafes and bars louches of la Boca. But by then, Eduardo Arolas was in his last resting place, the cemetery of Saint-Ouen in Paris where Juan Carlos Cobián and Genaro Espósito together brought flowers to the tomb of their old friend.

|

El Tano Genaro with the singer Doddy Combes (from the Paris nightclub Bagatelle) on tour in the summer of 1939 at Club Palm Beach in Cannes

|

Before returning to Buenos Aires, Cobián told Genaro he would like to stay in Paris where the tango was still popular. Perhaps he felt that the situation was somehow deteriorating in Argentina and the city of light was very appealing to him. In any case, el Tano Genaro was enthusiastic of having Juan Carlos Cobián with him as the director of his orchestra. (12) As the turn of events would demonstrate, it was a good decision for Cobián to return to Buenos Aires because echoes of the conflict to come started to pervade insidiously the surface of the light heartedness of the Paris of 1937. |

The noises of war were not for nothing. After the annexation of Austria, the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1938, in turn Poland would be overwhelmed and torn apart by the main evildoers of the 20th century, Hitler and Stalin. This time though, England and France had to honour their defence treaty with Poland and therefore the beginning of the Second World War.

Genaro Espósito was on a tour of the French Riviera when the order of general mobilization came about. He returned to Paris only at the end of September. Prior to this, he was urged by his son Teodoro, my half brother, to come back to Argentina, but my Dad, who took the French nationality, was too much in love with Paris. And, like everyone else, he didn’t believe that France would be overrun and occupied by the Germans for the following four years.

Most of the night clubs were closed. Genaro was out of work. His savings dwindled to practically nothing. He had to resort to the sale of his piano, jewelry, silver – everything that could buy food. In the summer of 1943, he was reduced to play his bandoneon for the Germans on leave from the Russian front on the bateaux mouches of Paris plying the Seine River. He was paid in food. At the end of that same year, a group of starving artists and musicians decided to organize a tour of the towns of southern France. He left at the end of November 1943 and we didn’t hear of him again until the first week of January 1944 when a telegram arrived that said “Not feeling well. Have to interrupt the tour”.

A few days later, the doorbell rang. When I opened the door, I hardly could recognize my father. His graying beard was several days old. Around his shoulder were strapped his two bandoneons. This memory really never left me. He was put in bed right away, delirious with fever. After a few days, he had to go the hospital. He was diagnosed with pneumonia, aggravated by emphysema. He was put under an oxygen tank. After five or six days, he seemed to get better but on January 24, 1944, he passed away at L’Hopital Broussais of Paris , and was buried in the Thiais cemetery, in a southern suburb of Paris , to rest for eternity alongside my Mother.

.

Genaro Espósito was on a tour of the French Riviera when the order of general mobilization came about. He returned to Paris only at the end of September. Prior to this, he was urged by his son Teodoro, my half brother, to come back to Argentina, but my Dad, who took the French nationality, was too much in love with Paris. And, like everyone else, he didn’t believe that France would be overrun and occupied by the Germans for the following four years.

Most of the night clubs were closed. Genaro was out of work. His savings dwindled to practically nothing. He had to resort to the sale of his piano, jewelry, silver – everything that could buy food. In the summer of 1943, he was reduced to play his bandoneon for the Germans on leave from the Russian front on the bateaux mouches of Paris plying the Seine River. He was paid in food. At the end of that same year, a group of starving artists and musicians decided to organize a tour of the towns of southern France. He left at the end of November 1943 and we didn’t hear of him again until the first week of January 1944 when a telegram arrived that said “Not feeling well. Have to interrupt the tour”.

A few days later, the doorbell rang. When I opened the door, I hardly could recognize my father. His graying beard was several days old. Around his shoulder were strapped his two bandoneons. This memory really never left me. He was put in bed right away, delirious with fever. After a few days, he had to go the hospital. He was diagnosed with pneumonia, aggravated by emphysema. He was put under an oxygen tank. After five or six days, he seemed to get better but on January 24, 1944, he passed away at L’Hopital Broussais of Paris , and was buried in the Thiais cemetery, in a southern suburb of Paris , to rest for eternity alongside my Mother.

.